Writing a sentence seems like a simple thing – just figure out who is doing what, and write it! Right. Except it is not that simple for an Aspie…

This seems incomprehensible to many teachers, parents, and any ‘outside observers’. How come an Aspie is fully capable of presenting a coherent, detailed explanation of something without any preparation, but when asked to write a sentence or two on that same topic, they are unable to produce one? How come that when asked a question, an Aspie student can speak for 15 minutes, giving exhaustive, accurate answer, but will only put down a single word as a response to the same question on a written test?

It does not seem credible – to the teachers or parents – that this could be possible. ‘Just write down what you said!’ tends to be the response/command/advice, but it just does not work like that. I do not know how or why, but I have seen it and experienced it. Needless to say, this only leads to very high levels of frustration among both sides…

Many professionals in this field are studying this, and doubtlessly, there are many excellent theories about why or how this occurs. I do not attempt to address that here – I just hope to look at the mechanics of how this can be overcome… at least, a tiny little bit!

First, the way language is taught is terribly important. It can mean the difference between practical illiteracy (at least, in the ‘output’ phase) on the one hand, and ‘functionality’ on the other. How can this be so?

Aspies tend to like to follow rules. Perhaps not everyone’s rules, perhaps they have a lot of difficulty decoding social rules, but – once a rule is understood and accepted, Aspies tend to derive comfort from adhering to them. This is true for language.

It is unfortunate that the current ‘model’ for teaching English (as a first language) in much of North America is the ‘whole language’ approach: this is the hairebrained idea that children will simply ‘absorb’ the rules of English when they are ‘exposed’ to them. Perhaps this may work for a small minority of kids. It certainly makes the teaching less laborious, because the teacher does not have to actually teach grammar, correct grammatical errors in written work (we are looking for substance, not grammar…). And, much more often than I would have liked, I have come across teachers who are not even able to follow simple rules of grammar themselves!

This is a major problem for Aspies: the rules are difficult to ‘absorb’ – especially when the teacher does not use proper grammar…. Constructing a proper sentence then becomes quite bewildering. Yet, many Aspies can master written language quite well, so there must be something else going on here.

Perhaps there is a different part of the brain that controls verbal and written expression. Or, perhaps many Aspies consider things that are ‘written’ to be ‘permanent’ – and therefore there is a much higher level of perfection that is required. I have asked many adult Aspies who have tremendous difficulties writing things, and there seem to be striking similarities among most of them.

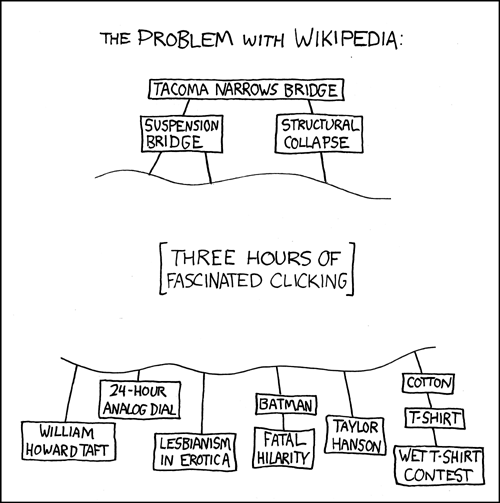

First, the idea. That is the easy part. In other words, the Aspie knows what he (the friends I questioned were all men) wants to write. The problem comes in the how to write it: they will put a word down, wonder if it is the most accurate one – and start ‘googling’ it. Wikipedia probably has some pretty good definitons of this – you should check it….

OK, refocus. Now you have the correct word. So, how do you fit it into the sentence correctly? Is that the right grammar? Perhaps you should ‘google’ that….

OK, refocus. You now have a noun and a verb, most likely in the proper grammatical structure. But it is nowhere near sufficient to capture the meaning… Perhaps it is time for lunch.

And so it goes. Not very productive, but, eventually, some semblance of a sentence will be produced.

So, how can one help a child learn to overcome this?

My personal exerience gave me some insight. I was lucky enough to be able to reproduce patterns – sound patterns and picture patterns. This helped me get selected for a language school when I was 8 years old… and while I was struggling to write basic sentences in my native tonngue, miraculously, I did not experience the same problem in the new languages.

Perhaps advice from a teacher helped:

‘Do not write what you want to say, write what you are able to say!’

With a limited vocabulary of less than 50 words, and only a rudimentary rules of how to construct a sentence according to the new language’s rules, the prospect of ‘writing a sentence’ became more managable! With only a limited number of permutations possible, selecting the best possible combination of them which most effectively gets the point across became easy!

When my older son got to a point in his schooling where he was expected to construct more than just simple sentences, he started having a problem. Trying to help him, I realized that he only had a very basic (and somewhat flawed) idea of how English grammar works….

Solution?

Basic textbook of Latin!

The reasons for selecting Latin were many: from loan words down. But the most important reason was that the Latin grammar was very explicitly spelled out – and that the endings of the words would change, depending on what role in the sentence that word played. This is very key – it reinforces the rules of grammar, and helps figure out how to use them to construct a sentence.

My goal was not to teach my son Latin. As a matter of fact, we spent no effort on memorizing vocabulary – we only focused on learning the rules for ‘flexing’ the words: what does a particular ending mean – and what it tells us about the role this word plays in the sentence. This skill was then easy to transpose into English sentence composition.

Yes – sentence composition. Because that is how it has to be approached – this word is the subject. This word describes the subject. This word is the verb. This word describes the verb…. and so on.

For younger kids, it might help to use tools: on small, rectangular pieces of card paper, print a limited number of words related to the topic the child needs to write a sentence about. Depending on the kid, start with 20-30. Separate them according to their role in the sentence – it migh be very helpful to colour code them. Nouns in one colour, verbs on another, pronouns, adverbs…so on. Or, just separate them into piles.

Then, when the child needs to write a sentence, let her/him pick out the right words and ‘build’ the sentence out of the ‘card words’. Since only a very limited number of words are available, the child must be told the task is not to ‘answer the question’ – because that might seem impossible! Explain to the child that the goal is to ‘build the best possible answer out of these words. It will not be perfect – and it is not expected to be! Make it a game to try to create the best ‘best fit’ that could be done from this set of ‘card words’.

Once the sentence is created, the child can copy it – and use it as the answer.

The word-pool can be altered, based on the topic. It can be increased or decreased, based on the child’s needs: the more difficulties, the fewer words to pick from. It is a tedious process, but it does work – or, at least, it worked in several instances when I have used it (not just with my own kids).

My personal opinion is that it teaches several things:

- By limiting the pool of words, it makes ‘finding the right word’ easier – by making it OK to settle for the ‘best available word’.

- By forcing the use of ‘different types’ (as signified by colours/piles of words, based on role played in the sentence) of words, the Aspie reinforces the proper use of grammar

- This exercise builds one’s confidence in their ability to form sentences – which is much more important than most educators acknowledge.

- Perhaps most importantly, it creates the habit to ‘write what you can, not what you want to’

It is not perfect, but this might help overcome the obsessive need to only write an ‘impossibly perfect’ sentence…

Learning to write is not easy for people with Asperger syndrome. There are many obstacles in their way: from mechanical difficulties, to ‘holding onto their thought long enough to write it down’. Add the desire for perfectioninsm in written expression….

Following the suggestions of professionals who know the child is the best way to help him or her learn to overcome the difficulties which are part and parcel of Aspergers. Yet, if nothing seems to work, frustration levels are building, the child is unhappy… I know there were times when I would have tried just about anything! And letting the child help sort the words just might take an edge off the frustration.